(a) Try to find the dog in this image. (b) Can you make out any forms from the splotches in this image? (c) Though it may be hard to tell, both of the smaller rectangles are the same shade of gray. (d) This image appears to be a gradient gray bar over a similar gradient background. However, if you cover the background you will see that the bar is a uniform shade of gray.

Everyone loves a good optical illusion. The world of social media was simultaneously thrilled and frustrated by the apparently color-changing dress that appeared in 2015 (discussed here, along with 11 other optical illusions). We enjoy optical illusions when they present as a fun trick to discuss with our friends. You may enjoy them less when they’re hiding in your patient’s CBCT scans, however.

“When digital radiography came out 20 years ago,” John A. Khademi, DDS, MS, explains, “misinterpretation was rampant. Lots of fillings and crowns were inappropriately re-done by dentists who misinterpreted artifactual findings as recurrent decay. They took out the filling or cut off the crown and, lo-and-behold—no decay.”

“The problem with CBCT can be likened to the chicken and the egg,” he continues. “With periapical radiography, we all went to dental school and learned about how radiographs are made and how to interpret them: what decay looked like, crowns, fillings, etcetera. As specialists we went to endodontic school with people who had experience and we could interpret the radiography and get feedback from those with expertise: ‘This subtle finding means x, that finding means y.’ There was domain expertise and skill-set transfer. But CBCT was deployed into private practice completely devoid of any academic understanding of the image-generation process. There was an illusion of domain expertise as the medium looked familiar, but it wasn’t, leading to interpretive errors.”

Without that academic background in CBCT, clinicians are working backward to develop their expertise. Dr Khademi’s new book, Advanced CBCT for Endodontics: Technical Considerations, Perception, and Decision-Making, is a step toward filling the gaps in the industry’s current knowledge regarding CBCT interpretation. In it, he confronts and explains how the principles of human perception affect how we interpret CBCT imagery, much like how it affects what we see in those tricky optical illusions passed around via social media.

Without that academic background in CBCT, clinicians are working backward to develop their expertise. Dr Khademi’s new book, Advanced CBCT for Endodontics: Technical Considerations, Perception, and Decision-Making, is a step toward filling the gaps in the industry’s current knowledge regarding CBCT interpretation. In it, he confronts and explains how the principles of human perception affect how we interpret CBCT imagery, much like how it affects what we see in those tricky optical illusions passed around via social media.

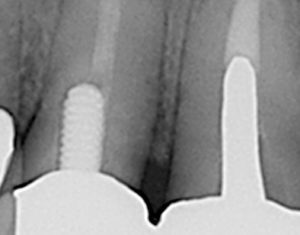

“Endodontists bring to the interpretive process a bias for interpretation that is influenced by other findings in the imaging,” Dr Khademi explains. “[In the figure to the right], the poorly done endodontics hits the endodontist immediately and biases the interpretation of the periapical area, increasing the chances that he or she will call an abnormal finding. This detection and recognition happens very quickly without effort and cannot be stopped. The clinician needs to then engage higher thinking and consider, ‘Are there any other explanations for these observations?’ The endodontist must recognize that all of the expertise he or she is bringing to the interpretive process is a double-edged sword.”

“Endodontists bring to the interpretive process a bias for interpretation that is influenced by other findings in the imaging,” Dr Khademi explains. “[In the figure to the right], the poorly done endodontics hits the endodontist immediately and biases the interpretation of the periapical area, increasing the chances that he or she will call an abnormal finding. This detection and recognition happens very quickly without effort and cannot be stopped. The clinician needs to then engage higher thinking and consider, ‘Are there any other explanations for these observations?’ The endodontist must recognize that all of the expertise he or she is bringing to the interpretive process is a double-edged sword.”

Use this attentional template to find the form hiding in image b at the top of this article.

The familiarity endodontists have with certain findings form attentional templates, similar to how we recognize familiar shapes or patterns in optical illusions. “We have an attentional template for recurrent decay underneath a crown from film radiography,” Dr Khademi says. “This attentional template hits us very fast with the perceptual process, and we mistake this familiarity and the speed with which we recognize this pattern for accuracy. However, this isn’t the film domain; it’s the digital domain, and a host of new artifactual imaging findings are possible.”

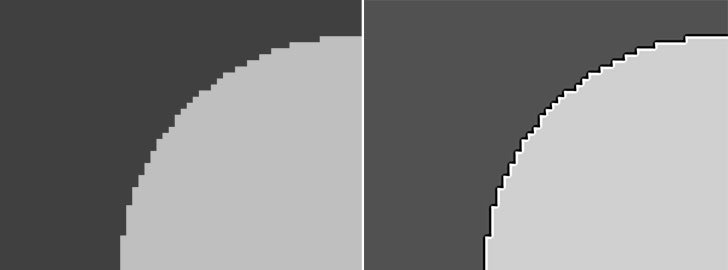

In the image to the right, we see what looks like recurrent decay and/or open margins. However, what is seen is actually an image-processing artifact called ringing artifact. This artifact mimics the attentional template for recurrent decay and open margins. The images below show this particular artifact simulated by software. Without knowledge of image processing and related artifacts specific to CBCT, the endodontist cannot differentiate between what is real and what is illusion, increasing the opportunity for inaccurate diagnoses.

In the image to the right, we see what looks like recurrent decay and/or open margins. However, what is seen is actually an image-processing artifact called ringing artifact. This artifact mimics the attentional template for recurrent decay and open margins. The images below show this particular artifact simulated by software. Without knowledge of image processing and related artifacts specific to CBCT, the endodontist cannot differentiate between what is real and what is illusion, increasing the opportunity for inaccurate diagnoses.

How Do We Improve?

Clinicians must develop a new internal database not biased by the attentional templates developed through periapical radiography because the differences between the mediums mandate that much of that knowledge does not translate, and any attempt to make it translate may jeopardize success. Dr Khademi lays out the steps for building this knowledge:

“What endodontists must develop in terms of an internal database is the large number of artifactual findings that have no analog in PA radiography and can mimic pathologic findings, the very wide range of normal periapical findings at CBCT compared to projection radiography, and better language to describe imaging findings in a way that highlights inferences and uncertainty.”

All of these topics are covered in Dr Khademi’s book. However, he also emphasizes that endodontists must be open to feedback as well. “In private practice, we are generally alone and, because we aren’t the ones to extract teeth later, we don’t get feedback on our interpretive errors.”

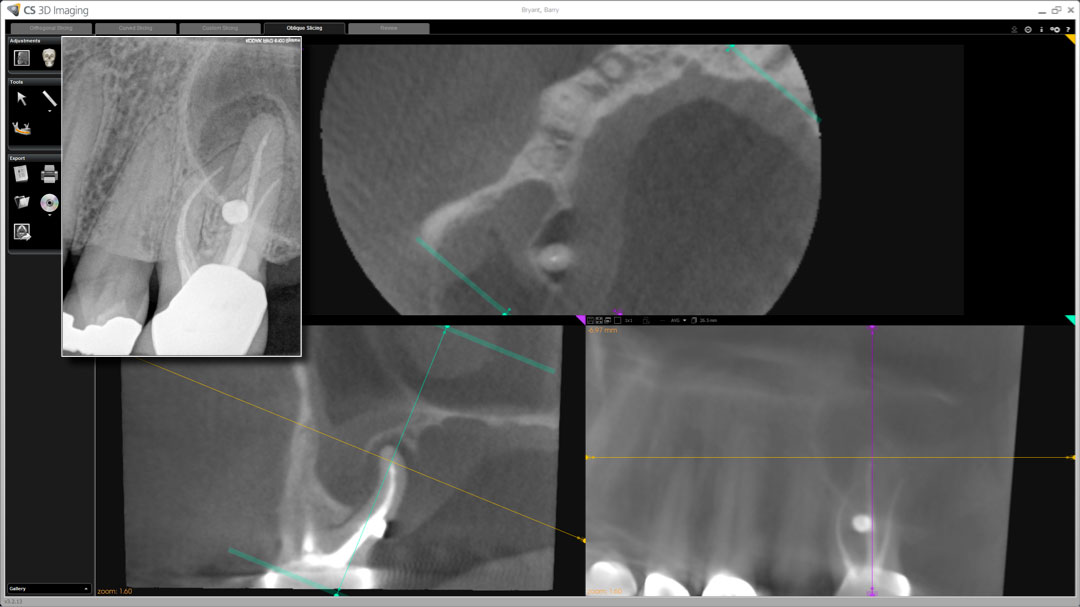

In his book, Dr Khademi shares an example of a case (featured above) that he managed in 2010 right after installing a CS-9000 (Carestream Dental) imager in his practice. The periapical projection radiography showed radiolucent findings possibly encompassing two or three roots and likely short root fillings of the mesiobuccal root, among other findings. The CBCT study showed radiolucent changes surrounding the palatal root, so Dr Khademi recommended extraction and replacement with an implant and referred the patient to a periodontist. The periodontist called back and said, “You may want to treat the necrotic lateral incisor.” While this particular case demonstrates the issue of satisfaction of search—the idea that once a meaningful interpretation is found, we stop looking—it also illustrates the importance of feedback.

“For us to experience failure we need to know that we have failed, and that requires feedback,” Dr Khademi explains. “Here, in reference to my own interpretive failure on the necrotic lateral incisor, I would have never known that I had missed that finding had the periodontist not given me that feedback. Lacking feedback, there is some evidence that learning simply will not occur.”

When reading Dr Khademi’s book for the first time, some clinicians may find unsolicited feedback when they recognize artifacts explained in the text as findings they may have seen in their own patients’ imaging. However, as with the famous dress that some of us incorrectly saw as white and gold, the best part of finding out you’re wrong is learning how to be right.

John A. Khademi, DDS, MS, is an adjunct assistant professor of endodontics at Saint Louis University. He received his dental degree from the University of California San Francisco and his certificate in endodontics and MS in digital imaging from the University of Iowa. He previously wrote software for laboratory automation, instrument control, and digital imaging. He lectures internationally about CBCT, clinical trial design, outcomes, and conventional endodontic techniques. As a Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) member for over 25 years, his background in medical radiology allows him a perspective shared by very few dental professionals. He maintains a private practice limited to endodontics in Durango, Colorado.

John A. Khademi, DDS, MS, is an adjunct assistant professor of endodontics at Saint Louis University. He received his dental degree from the University of California San Francisco and his certificate in endodontics and MS in digital imaging from the University of Iowa. He previously wrote software for laboratory automation, instrument control, and digital imaging. He lectures internationally about CBCT, clinical trial design, outcomes, and conventional endodontic techniques. As a Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) member for over 25 years, his background in medical radiology allows him a perspective shared by very few dental professionals. He maintains a private practice limited to endodontics in Durango, Colorado.

Advanced CBCT for Endodontics: Technical Considerations, Perception, and Decision-Making

Advanced CBCT for Endodontics: Technical Considerations, Perception, and Decision-Making

John A. Khademi, with contributions by Gary B. Carr, Richard S. Schwartz, and Michael Trudeau

Imaging has always been, and will continue to be, a central technology behind decision-making and outcome assessment in endodontics. However, as this technology changes, so must our interpretation of the imaging itself. CBCT images are radically different from periapical projection radiography, and their interpretation is informed by our perception and cognition, which is by no means perfect. Conventional methods of radiograph interpretation cannot be extended to CBCT imaging, so this book encourages endodontists to develop a sound technical and theoretical understanding of CBCT. The authors compare the capabilities of modern CBCT imaging with traditional radiography and also present vital information about image interpretation and perception to increase competence and confidence in CBCT interpretation and minimize overdiagnosis and subsequent overtreatment.

352 pp; 688 illus; ©2017; ISBN 978-0-86715-720-8 (B7208); US $148

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: June – Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: July | Quintessence Publishing Blog