Few technologic advancements in human history remain the same forever. As improvements are made, technology changes and evolves until, in some cases, the present-day technology looks nothing like its predecessor: compare the device you’re reading this on to the Z3 or the Manchester Baby—the differences are quite stark, especially if you’re using a handheld device. But some inventions achieve such a high level of innovation that they leave little room or need for further improvement. Such is the case with Professor F. J. Kratochvil’s RPI system for removable partial denture (RPD) design, which has remained in use worldwide since its introduction in 1963 and continues to influence modern RPD design.

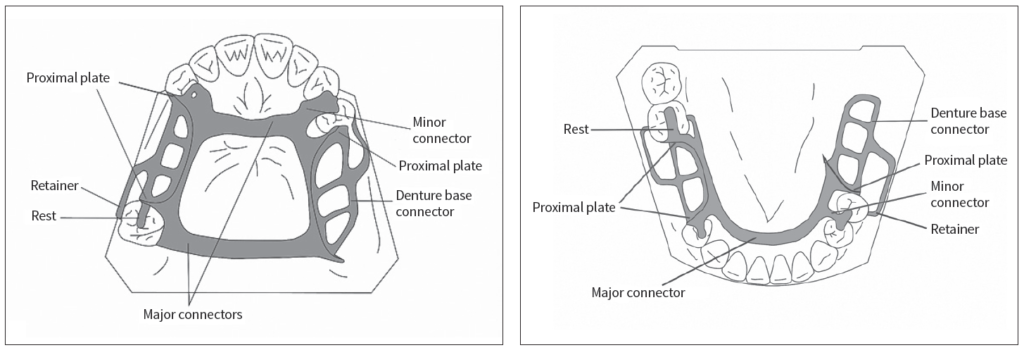

“Few people changed the practice of prosthodontics like Prof Kratochvil did,” explains Ting-Ling Chang, DDS, Section Chair of the Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the School of Dentistry of the University of California, Los Angeles. “Prof Kratochvil’s most notable contribution to our discipline was the development of the so-called ‘RPI system’ of RPD design: a clasp assembly consisting of a rest, a proximal plate, and an I-bar retainer. He was one of the first to recognize the importance of biomechanics in RPD design and used these principles to develop a whole new design philosophy. His initial article in The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry in 1963 (and later his textbook) forever changed the way dentists approach partial denture design.”

Fifty-five years later, Dr Chang has authored a new textbook titled Kratochvil’s Fundamentals of Removable Partial Dentures along with two of her colleagues from the UCLA Division of Advanced Prosthodontics: Assistant Clinical Professor Daniela Orellana, DDS, and Distinguished Professor Emeritus John Beumer III, DDS, MS. The book is a testament to the enduring design of Prof Kratochvil’s RPI system, and it demonstrates a rare instance of success in the challenge of developing innovations that go beyond merely improving upon present technology for the short term and instead achieve a level of innovation with lasting relevance in a rapidly changing field like prosthodontics.

The Difference in the Design

“Many of Prof Kratochvil’s original design features have been incorporated into other current RPD designs,” Dr Beumer explains. “For example, almost all modern designs incorporate proximal plates and use the mesial rest concept when restoring edentulous extension defects. Currently, the only major difference currently between popular designs is the type of retainer used. Two other popular retainer types besides the I-bar include the circumferential clasp in association with the RPA system and the wrought wire retainer.”

“The main difference between Prof Kratochvil’s RPI system and other RPDs used today is the biomechanical consideration and the favorable outcomes offered by the RPI design, especially for extension-base RPDs,” Dr Chang adds.

That biomechanical consideration inherent in the design of the RPI system is exactly what made Prof Kratochvil’s work so groundbreaking in the 1960s and what maintains its relevance today. “The reason Prof Kratochvil’s design has remained scientifically sound,” Dr Orellana explains, “is because the biomechanics of teeth and RPDs have not changed. Before him, RPDs were considered a transitional appliance to complete edentulism. Prof Kratochvil was one of the first clinicians to recognize the importance of biomechanical consideration in RPD design because he was thinking about RPDs as a long-term versus transitional treatment. One of the most significant improvements his system provides over others is that the RPI design is a stress-relieving design that allows for rotation of the appliance without exerting detrimental forces to the abutment tooth, which was a complete change from the effects of previous RPD designs on the abutment teeth.”

(a) Placement of the rest adjacent to the edentulous extension area may produce a tipping force during function, which opens the contact between the abutment tooth and the adjacent tooth. (b) Moving the rest away from the edentulous area produces a direction of force that tends to maintain contact with adjacent teeth, resulting in multiple-tooth support and acceptable directions of force application.

Proximal plates are plates of metal in contact with proximal surfaces of the abutment teeth. They should extend 2 mm onto the mucosa of the alveolar ridge (arrows).

Indeed, RPDs have long borne the reputation of being detrimental to the remaining dentition when employed long-term. “This misconception,” Dr Beumer explains, “is largely based on clinical reports published in the 1950s and 1960s before Prof Kratochvil developed his system. During this time, the acrylic resin portion of the RPD frequently came into contact with the surfaces of the abutment teeth, and, after a period of use, the porous acrylic resin would become infiltrated with oral microorganisms, predisposing the abutment teeth to caries and periodontal breakdown. In Prof Kratochvil’s design, the use of a metal proximal plate mitigated this risk because the metal is nonporous. Biomechanics played its role as well, but I think the use of the metal proximal plate was equally impactful in improving outcomes because of the additional feature that its use united and consolidated residual arch segments, permitting a wider and more equitable distribution of occlusal forces. Of course, patient oral compliance continues to be the most important factor in the survivability of any prosthetic option we employ, whether it be fixed, removable, or implant-retained. Patients who have a history of multiple tooth loss are often noncompliant with regard to oral hygiene, and this factor was often not taken into account with early RPD clinical outcome reports.”

Dr Chang expounds on the biomechanical improvements offered by Prof Kratochvil’s design and how that can impact the health of the abutment teeth: “The reason the general perception persists that RPDs will compromise the health of the abutment teeth is because many RPDs delivered today include little to no consideration of the biomechanical aspect during their design. Laboratory surveys show that many RPD designs are done by laboratory technicians who have never seen the patients or the clinical situations. Back in the clinic, many clinicians feel less confident in designing RPDs because more and more dental schools have and continue to reduce the curriculum time devoted to removable prosthodontics. Studies show that a well-designed RPD does not compromise the health of the abutment teeth in patients with good oral hygiene. The two key factors there are: (1) a well-designed RPD and (2) good patient oral hygiene. As clinicians, unfortunately we can only truly control the first factor, and this book is written to promote that goal and help readers provide quality prostheses for their patients so we can change this widespread misperception.”

(a) The circular anteroposterior strap is favored for most maxillary RPDs because it combines maximum rigidity and strength with minimum bulk. The rests on the canines provide indirect retention. (Courtesy of Dr A. Davodi, Beverly Hills, California.) (b) The position of the posterior strap should be anterior to the vibrating line and terminate adjacent to but just short of the hamular notch. As such, the acrylic resin of the denture base can cover the tuberosity and smoothly transition with the RPD framework.

RPDs Versus FPDs Versus Implants

No modern conversation about treatment options for restoring missing teeth would be complete without mentioning implants, and it does seem to correlate that as interest in implants among both clinicians and patients increases, interest in and education devoted to RPDs decreases. Implants are largely discussed and positioned as the ideal solution for missing teeth: a fixed, subgingival replacement system that to the patient looks and behaves like natural teeth.

“Implant technology is very popular among clinicians,” Dr Chang explains, “because of its profitability and high patient interest. But as clinicians we also need to acknowledge the fact that implants are not the best option for everyone. In fact, there are many circumstances where RPDs are the best option for the patient. Just to name two: patients with a large deficiency in hard and soft tissue, making it challenging to achieve optimized esthetics using fixed partial dentures (FPDs) or implants, as well as patients with systemic health factors at play that contraindicate implants or financial limitations that prevent both FPDs and implants. Likewise, it is important to discuss situations where a combination of modalities may be desirable. For example, some patients cannot afford a fixed prosthesis supported by multiple implants. Instead, we can consider placing one or two implants and an RPD for an implant-enhanced RPD solution.”

(a) Pneumatized maxillary sinus. (b) Resorption of bone over the inferior alveolar nerve. Both preclude implant placement in the absence of site enhancement.

“As a clinician,” Dr Orellana emphasizes, “it is important to integrate individual clinical expertise with the best available scientific evidence during the decision-making process for patient care.”

As someone whose clinical experience spans both before and after the introduction of dental implants, Dr Beumer offers a unique perspective: “Osseointegration is the most impactful phenomenon introduced to the dental profession in my career,” he states, “and has been widely promoted to the public by commercial interests. However, as I frequently remind my students, the functional outcomes offered by implant-supported prostheses frequently are no better than the functional outcomes offered by RPDs. I have even emphasized this point in my textbook Fundamentals of Implant Dentistry: Prosthodontic Principles (Quintessence, 2015). Moreover, RPDs frequently provide a superior esthetic outcome when compared with implant options. Given this information and the cost difference, most patients will choose RPDs. However, if they have the financial resources, many patients prefer to be restored with a fixed implant–retained and supported prosthesis.”

(a) Bilateral extension-base RPD. (Courtesy of Dr R. Faulkner, Cincinnati, Ohio.) (b) Bilateral extension areas restored with a single implant connected to a natural tooth abutment. The mastication efficiency of the RPD is equivalent to that obtained with the implant-supported FDP.

So when treatment planning, if a patient is a suitable candidate for an RPD or implant-supported prosthesis and the expected functional outcomes are the same, how do clinicians guide their patients through the treatment options? When one of the major differences affecting patient choice—cost—results in higher profitability for the clinician, how do clinicians present the options fairly and appropriately?

“With regard to patient satisfaction,” Dr Beumer explains, “I present all treatment options to the patient with their pros and cons and let the patient make the choice. I also provide input and give them my opinion as to which option best meets their needs. In my experience, most patients select a an RPD, the main reasons being cost, insufficient bone to receive implants in the desired sites, and the prospect of the multiple surgeries needed for implants. I also emphasize the need to consider conventional treatment options when I present my lectures on implant prosthodontics to students.”

“As a clinician,” Dr Chang states, “I prefer the RPI system as my first choice if there is no other contraindication. RPI RPDs offer superior esthetics and favorable biomechanical outcomes. It is a simple, elegant, and very hygienic design compared with other clasp assemblies. But the consideration of prosthodontic tooth replacement treatment options for partially edentulous patients always starts with listening to the patient first. Each patient has unique expectations and prior experiences; understanding their concerns and their priorities should always be your first step. The prosthodontic process is a patient-centered and shared decision-making process. In many cases, RPD may be the most suitable tooth replacement option due to various patient factors, and it is our duty as responsible prosthodontists to continue to offer this modality.”

(a to f) I-bar retainers provide superior esthetic results with minimal metal display. Only the tips are visible in most patients.

The Future of RPDs

With the rise in implant dentistry, there will be inevitable shifts in removable prosthodontics. One of these shifts has already presented itself in changes to education curricula in dental schools worldwide.

“We see reduced curriculum time devoted to RPDs in many dental schools, both in the classroom and the clinic, in order to free up curriculum time for emerging fields such as implant, esthetic, and digital dentistry in the DDS programs. But RPD treatment will never become obsolete because the need to restore partially edentulous patients will never go away; indeed, the partially and fully edentulous population will only continue to grow. That is why it’s important to offer other resources for clinicians and recent graduates such as reference books like our textbook as well as continuing education in RPDs.”

In addition to the changes in educational program design, advances in digital dentistry are also impacting RPDs and creating new and exciting possibilities.

“I think digital design and CAD/CAM technology is very exciting,” Dr Chang enthuses. “It is a very robust tool in improving efficiency and accuracy for our patient care. As an educator, I see a huge impact on creating fun and visual learning experiences using the digital design software. However, digital design and CAD/CAM will not change the RPD treatment principles or the RPI design concept.”

(a) Digitized master cast. (b and c) Virtually designed RPD framework. (d and e) Cast framework seated on the stone master cast. (f) Completed prosthesis seated intraorally. (Courtesy of Dr J. Jayanetti, Los Angeles, California.)

“I believe the Kratochvil RPI concept represents a near end point of the evolution of RPD design,” Dr Beumer states, “and that this system will represent the standard for the foreseeable future. The most recent innovations have addressed retainer designs, such as the wrought wire clasp (Brudvik) and the RPA system (Eliason), and both have employed proximal plates and the mesial rest concept. Also, the RPI system subsequently developed by Krol adopted all of Prof Kratochvil’s principles but differs only by a slightly shortened proximal plate.

“Prof Kratochvil was a logical, disciplined, and creative thinker who was willing to challenge the accepted dogmas of his day. It is interesting to note that when he first introduced his concepts, he was frequently criticized by the dental establishment. The points of innovation now—CAD/CAM and digital dentistry—will only affect the means of fabrication or adjudicate the treatment planning process. The design concepts promoted by Prof Kratochvil will continue to endure.”

While the peripheral aspects of RPD treatment, including the methods of fabrication, materials, and treatment-planning software, will continue to evolve, one important factor will stay the same—the biomechanics of the human dentition will not change, and therefore any rehabilitative solutions to replace the missing dentition will continue to follow these same rules. And as the partially edentulous patient population grows, RPDs will remain an important treatment option for clinicians dedicated to serving their patients’ best interests, meaning Kratochvil’s Fundamentals of Removable Partial Dentures will be an important addition to the shelves of prosthodontists for years to come.

Ting-Ling Chang, DDS, received her DDS from National Taiwan University in 1990 and completed two years of general practice residency and two years of prosthodontics residency training at National Taiwan University Hospital. She subsequently completed her advanced prosthodontics training in 1997 and maxillofacial prosthetics training in 1998 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Dr Chang is currently a Clinical Professor in Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry. Dr Chang is a Diplomate of the American Board of Prosthodontics.

Ting-Ling Chang, DDS, received her DDS from National Taiwan University in 1990 and completed two years of general practice residency and two years of prosthodontics residency training at National Taiwan University Hospital. She subsequently completed her advanced prosthodontics training in 1997 and maxillofacial prosthetics training in 1998 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Dr Chang is currently a Clinical Professor in Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry. Dr Chang is a Diplomate of the American Board of Prosthodontics.

Daniela Orellana, DDS, received her DDS from the Universidad Andrés Bello, Viña del Mar, Chile, in 2008. She subsequently completed a postgraduate training program in prosthodontics at the University of Michigan in 2013 and an implant fellowship at Louisiana State University in 2014. Dr Orellana is currently a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry.

Daniela Orellana, DDS, received her DDS from the Universidad Andrés Bello, Viña del Mar, Chile, in 2008. She subsequently completed a postgraduate training program in prosthodontics at the University of Michigan in 2013 and an implant fellowship at Louisiana State University in 2014. Dr Orellana is currently a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry.

John Beumer III, DDS, MS, received his DDS from the University of California, San Francisco in 1967. He subsequently completed his postgraduate training in oral medicine there in 1970 before continuing with postgraduate training in prosthodontics at UCLA. He is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry and was formerly chair of that division. Dr Beumer has published extensively in the scientific literature, including Maxillofacial Rehabilitation (Quintessence, 2011) and Fundamentals of Implant Dentistry (Quintessence, 2015–2016).

John Beumer III, DDS, MS, received his DDS from the University of California, San Francisco in 1967. He subsequently completed his postgraduate training in oral medicine there in 1970 before continuing with postgraduate training in prosthodontics at UCLA. He is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Division of Advanced Prosthodontics at the UCLA School of Dentistry and was formerly chair of that division. Dr Beumer has published extensively in the scientific literature, including Maxillofacial Rehabilitation (Quintessence, 2011) and Fundamentals of Implant Dentistry (Quintessence, 2015–2016).

Kratochvil’s Fundamentals of Removable Partial Dentures

Kratochvil’s Fundamentals of Removable Partial Dentures

Ting-Ling Chang, Daniela Orellana, and John Beumer III

In the 1960s, Professor F. J. Kratochvil recognized the importance of biomechanics in removable partial denture (RPD) design and used these principles to develop a new design philosophy. This “RPI system”—a clasp assembly consisting of a rest, a proximal plate, and an I-bar retainer—changed how clinicians approach partial denture design and is now used throughout the world. This textbook provides an overview of Kratochvil’s design philosophy and the basic principles of biomechanics it is based upon. Topics include components of RPDs and their functions, design sequences for maxillary and mandibular RPDs, and techniques for surveying and determining the most advantageous treatment position. A chapter dedicated to digital design and manufacturing of RPD frameworks highlights new technology in this emerging field. Additional topics include optimizing esthetic outcomes through attachments and rotational path RPDs as well as applying the RPI system to patients with maxillofacial defects. The authors provide illustrations of clinical cases throughout the book as well as an illustrated glossary of prosthodontic terminology. This textbook will prepare students and general practitioners to design and fabricate a biomechanically sound RPD framework for just about any dental configuration they encounter.

240 pp; 748 illus; ©2019; ISBN 978-0-86715-790-1 (B7901); US $108