The Smithsonian Institution in the United States has long been a top destination for tourists, but it is also a valuable resource for researchers. It houses over 138 million objects across 19 museums and galleries in 2 cities. In addition to the publicly exhibited works, the Smithsonian also maintains over 150,000 cubic feet of archives. It was in these archives that Lawrence Freilich, DDS, PhD, found the unique collection that would inspire his first book.

Records storage at the Smithsonian Archives. Could one of these boxes hold a 100-year-old fetal skeleton?

“I had retired from teaching at Georgetown University, so I was looking for a way to get involved with some research pertaining to what I had done while at Georgetown, which was on bone regeneration,” Dr Freilich recollected. “I was familiar with the Smithsonian and beginning to get an interest in anthropology, so I called and asked if they had anyone I could get in touch with. They connected me with Dr David Hunt, who is an expert in forensic anthropology.”

David Hunt, PhD, D-ABFA, is the Assistant Collections Manager for the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) and oversees all of their human skeletal collections. “My job is to facilitate outside research by connecting researchers to the collections that match their study goals, scheduling appointments for access, and answering any questions they may have,” Dr Hunt said. “We have a study going on right now that involves decorative filing of the teeth during the Mississippian era and another on the burial practices of Chinese immigrants working in the Alaskan salmon canneries in the late-1800s. Typically I have 65–70, sometimes over 100, external researchers who come over the course of the year and usually during the summer.”

Dr Freilich was one of those researchers who floated in without a clear idea of what he was looking for. “I asked if [Dr Hunt] had any specific projects I could get involved with, and he said there was a European anthropologist who had come in and started working on the collection of fetal skeletons they had. While I was looking at some of those skeletons I started picking up jaw bones and just became fascinated. I couldn’t recall any literature that displayed fetal jaw bones close-up and in detail, so we started putting together this study.”

That study became the Atlas of Fetal Jaw Development published this year. As explained in the first chapter of the book, the NMNH’s fetal collection was largely donated by doctors and academics so its specimens are exceptionally well documented in terms of age, gender, and ethnic origin. Dr Hunt described the history of this collection and how original collector Aleš Hrdlička obtained them as one of the most interesting parts of the study.

“Just to see and understand the breadth of how Hrdlička had the medical community involved and aware of this collection was impressive. Of course, [Franklin Paine] Mall and [Daniel Smith] Lamb were the two main contributors, but Hrdlička also obtained individuals from dozens of other obstetricians and gynecologists in the DC and Baltimore areas. The social milieu of today versus the early 1900s is different, so we no longer receive similar donations en masse. I think there are differences in the attitudes of how bodies are turned over for scientific studies than there were back in the turn of the century. There are numerous body laws that came about in the 1950s and ‘60s where unclaimed bodies are no longer the property of the state. They’re still the responsibility of the state, but unless there is paperwork explicitly giving permission to donate the body to science then the state must bury or cremate the body.”

The fetal collection involved in Dr Freilich’s study was, according to Dr Hunt, almost completely derived from pathological death or spontaneous, rather than elective, abortion. When a similar event occurs today, the family and the hospital must fill out paperwork through a body donation program in order to send the fetal remains to an institution like the Smithsonian. While the body laws are necessary to protect an individual’s right to bodily autonomy, the red tape has caused a shortage in cadavers available to the scientific community, making the NMNH’s fetal collection all the more impressive.

“The anatomical collections,” Dr Hunt said, “can serve as a template for archaeological study since we know who they were and what they died of. We have researchers come in to measure bone metrics from our anatomical collections to assist in determining the age and sex of other skeletal remains.”

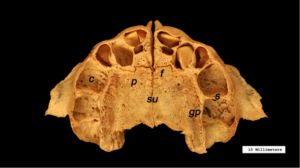

Occlusal view of the articulated maxillae in a later-stage fetus with teeth beginning to form. c, crypts; f, incisive fissure; gp, greater palatine nerves and vessels; p, palatine process; s, interdental septae; su, midline suture.

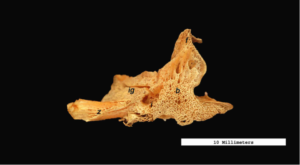

Buccal view of the right maxilla. Note the sponge-like surface of the bone. Anteroposterior length: 15.3 mm. b, body; f, frontal process; i, infraorbital foramen; ig, infraorbital groove; z, zygomatic process.

Anatomical collections are also useful for developmental studies, which is what piqued Dr Freilich’s interest. “The bone that becomes the tooth socket isn’t even present at 2–3 months of fetal age. So in the middle-stage fetuses—that’s 3-4 months in utero—you can observe the tooth sockets beginning to develop. Just the architecture and the surface anatomy of the jaw bones were fascinating to observe under the magnification of the camera lens. The surface structure of these bones appears sponge-like and displays an abundance of neurovascular channels. As the bones mature, those channels gradually diminish in size and are largely replaced by a more dense, sturdy bone tissue. This is necessary since the jaw bones and other skeletal elements need much more strength following birth.”

“What surprised me the most,” Dr Freilich said, “was how the skeletons were preserved and stored. They are all disarticulated as in fetal life and are stored in boxes. The entire skeleton is in one container. So it took some time to sort through the collection and find enough maxillae and mandibles in good shape from each age group to photograph.”

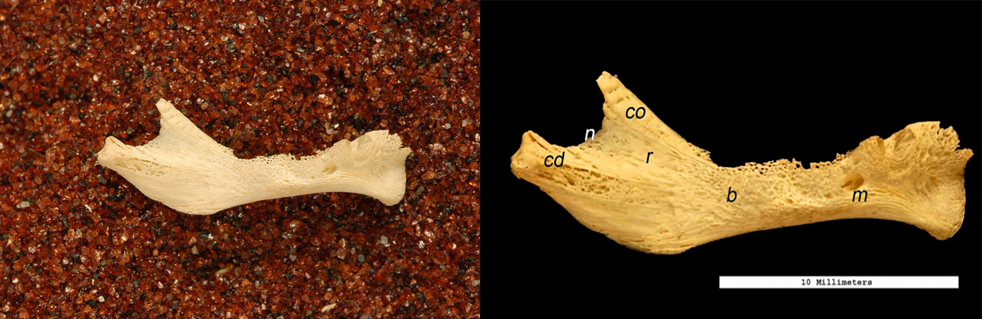

But photographing fetal bones isn’t easy. “You can put a thigh or an arm bone on a table and take a good picture very easily because they lie flat. But for the jaw bones we had to use pans of sand to angle the bones perfectly and keep them steady. We used tweezers to handle the bones because they are so fragile. When we were arranging the full skeletons in the pans of sand, the hardest part was the vertebrae. This is because in fetal life, each vertebral bone remains in three separate pieces, which are not joined yet. It was truly fascinating to see such tiny bones and handle them.”

Buccal view of the right mandible. Pans of sand were used to stabilize the bones for photography. During postproduction of the images, the sand was removed and markers were added to show scale and significant structures. Anteroposterior length: 20.6 mm. b, body; c, condyle; co, coronoid process; m, mental foramen; n, mandibular (sigmoid) notch; r, ramus.

For researchers interested in collaborating with the Smithsonian, Dr Hunt’s advice is to visit the website or call the manager of the collection you’re interested in. Appointments typically run 2–4 months ahead for scheduling, especially during the summer months.

For Dr Freilich, he simply sent in his curriculum vitae and the Department of Anthropology staff went about “matchmaking.” The result, Atlas of Fetal Jaw Development, is both a fascinating study on fetal jaw development and a testament to what discoveries open access in the research sector can foster.

Atlas of Human Fetal Jaw Development

Atlas of Human Fetal Jaw Development

Lawrence Freilich and David Hunt

This atlas presents a study of human fetal jaw development with a primary focus on the hard tissues of the maxilla and mandible. High-definition photographs are featured throughout of the well-preserved upper and lower jaw elements from the human fetal skeletons contained in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

72 pp; 83 illus; ISBN 978-0-86715-716-1 (I7161); US $37.99; iBook only