When patients notice something strange in their mouths, they will probably schedule an appointment with their general dentist. Even for potentially serious symptoms, most dental or health insurers require referrals before approving specialist visits. General dentists are and will always be the gatekeepers of patient access to oral health care—and that position carries with it a significant burden.

When Robert E. Marx decided to write a book on oral pathology for general dentists, the need was clear. “One of the obstacles preventing dentists from recognizing oral diseases in their patients is the de-emphasis of clinical pathology in many dental schools today. Pathology courses may not even require or use a textbook for more than ‘suggested supplemental reading.’ This de-emphasis creates dentists who are not trained on how to refer a patient to a specialist for treatment—or even which specialist is best for any particular finding.”

Sometimes the best education comes from hands-on experience. But when it comes to clinical pathology, the stakes can be high. Dr Marx describes some successes and failures of referring dentists.

Successful Diagnoses

A 5-year-old girl presented to a restorative dentist with a mass at the base of her tongue. The mass was difficult to see and required a thorough examination. A radioactive iodine scan confirmed the suspicion that the mass was a persistent lingual thyroid; further, it was the only thyroid the patient had. Had her doctors preemptively biopsied/excised the mass, the patient would have been sentenced to a permanent hypothyroid condition at a critical point in her growth and development.

Persistent lingual thyroid as the entire thyroid gland with no presence in the neck.

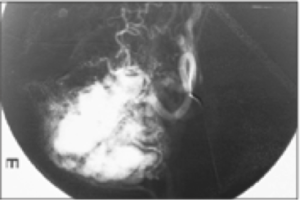

In another case, a pediatric dentist noted redness and puffiness of the gingiva on the lingual side of a first molar in an 11-year-old girl. During exploration of the lesion, the dentist provoked a small but pulsatile bleeding that required 5 minutes of pressure to stop. When Dr Marx and his team evaluated the lesion, angiograms identified a large arteriovenous hemangioma where, in his words, “the gingiva represented the crown of a volcano of a potential exsanguinating bleed.” The early identification allowed Dr Marx to embolize the lesion and remove it before it grew any larger; had the lesion gone unnoticed and untreated, the hemangioma could have ruptured and resulted in massive bleeding, as illustrated below in a similar case.

Angiogram of an arteriovenous hemangioma showing large vascular networks.

Young girl in hypovolemic shock from an arteriovenous hemangioma bleed.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lateral border of the tongue.

Dental hygienists are also capable of making these critical finds. One hygienist noticed an area of redness and firmness while performing a dental prophylaxis on the left lateral border of the tongue in a 61-year-old woman. Both the hygienist and dentist were suspicious enough of the lesion to refer the patient to Dr Marx, despite the fact that two physicians had previously identified it as a hypertrophied lingual tonsil. When Dr Marx biopsied the lesion, the results identified a squamous cell carcinoma. With a depth of invasion of 9 mm, the cancer required excision of the lesion as well as selective neck dissection. Thanks in part to the vigilance of the dental hygienist, the now–79-year-old patient is alive and well and continues to enjoy normal speech and eating.

Missed Diagnoses

But if every story had a happy ending, we wouldn’t need to be concerned about the status quo. Sometimes the find doesn’t come soon enough—other times, it comes far, far too late.

In one particularly frustrating case, a 45-year-old restorative dentist on the faculty of a major dental school presented with persistent redness of the anterior maxillary gingiva and frenulum. Despite impeccable plaque control—remember, the patient herself was a dentist—and her request for a biopsy, this squamous cell carcinoma was ignored and local periodontal care and topical antibiotic therapy continued for 2 years. When she was finally referred to Dr Marx, his biopsy identified the cancer that had by then invaded bone. An anterior maxillectomy was required.

Squamous cell carcinoma that was incorrectly diagnosed and treated as gum disease for 2 years, giving the cancer time to invade the bone.

A pyogenic granuloma—or could it be a cancer?

In a similar case, though one in which the patient did not have the advantage of a dental degree, a 42-year-old woman was diagnosed with a pregnancy tumor when a small, red, friable lesion emerged between her maxillary lateral and central incisors. After it was confirmed that the patient was in fact not pregnant, the working diagnosis was changed to a pyogenic granuloma. Over the course of treatment, the so-called pyogenic granuloma was removed twice but not sent for biopsy. By 20 months after her first presentation, the lesion had grown to the size of a tennis ball, and the patient had bilateral lymphadenopathy from squamous cell carcinoma. The required treatment included an anterior maxillectomy and bilateral neck dissections followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The patient remains disease-free a decade later but has undergone five reconstructive surgeries so far.

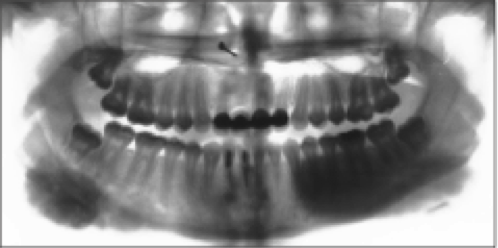

A final case demonstrates the many levels of care at which patients are vulnerable to misdiagnosis. An 18-year-old girl with a hard mass at the left angle of the mandible was diagnosed by her primary care physician as having mumps, even though the mass was attached to the angle of the mandible, not the parotid gland, and the patient had no fever, malaise, or anything else that would suggest mumps. After 9 months, the physician referred her to a dentist with the complaint of “numb lip.” The numb lip was incorrectly attributed to impacted third molars, and another 6 months transpired before a referral was made to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. The surgeon recognized the irregular bony mass as a probable osteosarcoma, which Dr Marx’s biopsy later confirmed. Despite surgery and chemotherapy, the patient died from diffuse metastasis shortly before her 21st birthday.

Osteosarcoma of the mandible as seen on a panoramic radiograph.

How to Move Forward

No one can go back in time and change a mistake that was made. What we can do is arm ourselves with the knowledge and tools necessary to do better the next time around. Dr Marx had the stories above in mind when he wrote his book Oral Pathology in Clinical Dental Practice. His goal in writing this book was not to produce a 700-page textbook for oral pathologists or maxillofacial surgeons on every possible finding, with detailed protocols for their management (that has already been done). Instead, his intent was to put potentially life-saving information into a format that would be accessible for the dental hygienist performing a routine cleaning who is in an ideal position to track changes in a patient’s oral health over time; for the general dentist whose gut instinct may be saying that a patient’s lesion doesn’t quite fit the textbook definition for a common condition and warrants a second opinion for ease of mind; and for the specialist who receives a referral for a prosthodontic rehabilitation that has already been cleared by the general dentist, but notices a potential issue that had not been previously managed and is now responsible for addressing it. This book empowers dental professionals across the spectrum of disciplines by giving them the information they need to recognize when something is wrong and to know what to do next.

“Dentists and their dental hygiene team historically have been the great identifiers of oral diseases,” Dr Marx emphasizes. “This book is dedicated to those practitioners who have picked up on diseases and conditions early, thus saving their patients from disease progression, deformity, and at times, even death. But it is also dedicated to those dentists who may have missed the early signs or obvious diseases while focusing exclusively on the dentition. It is hoped that this book will provide examples and guidance as well as the encouragement to be a diagnostician before being a treatment provider.”

Dr Marx’s aim is for his book to help each dentist, dental hygienist, and specialist become a more complete oral health care professional and, in doing so, maybe save a life or two.

Robert E. Marx, DDS, is Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. He is a well-known educator, researcher, and innovative surgeon who has pioneered new concepts and treatments for pathologies of the oral and maxillofacial area as well as new techniques in reconstructive surgery. The first edition of his textbook Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment (Quintessence, 2012) won the American Medical Writers Associations Prestigious Book of the Year award, and two of his other textbooks, Oral and Intravenous Bisphosphonate–Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: History, Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment, Second Edition (Quintessence, 2011) and Atlas of Oral and Extraoral Bone Harvesting (Quintessence, 2009), have both been bestsellers. His many prestigious awards, including the Harry S. Archer Award, the William J. Giles Award, the Paul Bert Award, the Donald B. Osbon Award, and the Daniel Laskin Award, attest to his dedication and commitment to the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Robert E. Marx, DDS, is Professor of Surgery and Chief of the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. He is a well-known educator, researcher, and innovative surgeon who has pioneered new concepts and treatments for pathologies of the oral and maxillofacial area as well as new techniques in reconstructive surgery. The first edition of his textbook Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment (Quintessence, 2012) won the American Medical Writers Associations Prestigious Book of the Year award, and two of his other textbooks, Oral and Intravenous Bisphosphonate–Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: History, Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment, Second Edition (Quintessence, 2011) and Atlas of Oral and Extraoral Bone Harvesting (Quintessence, 2009), have both been bestsellers. His many prestigious awards, including the Harry S. Archer Award, the William J. Giles Award, the Paul Bert Award, the Donald B. Osbon Award, and the Daniel Laskin Award, attest to his dedication and commitment to the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Oral Pathology in Clinical Dental Practice

Oral Pathology in Clinical Dental Practice

Robert E. Marx

While most dentists do not perform their own histologic testing, all dentists must be able to recognize conditions that may require biopsy or further treatment outside the dentist office. This book does not pretend to be an exhaustive resource on oral pathology; instead, it seeks to provide the practicing clinician with enough information to help identify or at least narrow down the differential for every common lesion or oral manifestation of disease seen in daily practice as well as what to do about them. Organized by type of lesion, mass, or disease, each pathologic entity presented includes the nature of the disease; its predilections, clinical features, radiographic presentation, differential diagnosis, and microscopic features; and the suggested course of action for the dental practitioner as well as the standard treatment regimen. In keeping with the concise nature of the text, all but the rarest disease entities include at least one photograph to illustrate the clinical condition. This book distills the comprehensive information from Dr Marx and Dr Diane Stern’s award-winning pathology reference text (Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology: A Rationale for Diagnosis and Treatment, Second Edition [Quintessence, 2012]) into practical guidelines for restorative and general dentists everywhere.

376 pp; 425 illus; ©2017; ISBN 978-0-86715-764-2 (B7642); US $98

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: October | Quintessence Publishing Blog

Pingback: Quintessence Roundup: November | Quintessence Publishing Blog