The three camera systems (Nikon, Canon, and Olympus) recommended by Dr Sheridan for clinical photography.

It is common practice in many dental clinics to perform a New Patient exam and create records that capture the exact status of the patient’s dental health. These records generally include radiography, a detailed patient history, and, in some practices, clinical photographs. Since the invention of digital cameras, clinical photography has become progressively more common in orthodontic and esthetic dentistry but not general dentistry. However, Australian dentist Peter Sheridan, AM, BDS, MDS, FICD, hopes to make clinical photography standard practice in every dental clinic.

“The standard assessment tools such as charting, clinical notes, and radiographs have not changed significantly in 40 years, although computerization has modified the process somewhat,” Dr Sheridan explains. “But the profession largely ignores the fact that none of these records show the mouth as it actually appears at the time of examination or treatment. From both a best-practice and a risk-management perspective, the use of routine clinical photography augments these other records and dramatically fortifies the dentist’s evaluation of the patient’s presenting condition and the treatment options. Photographs before, during, and after treatment can have enormous value in increasing patient understanding and acceptance of treatment.”

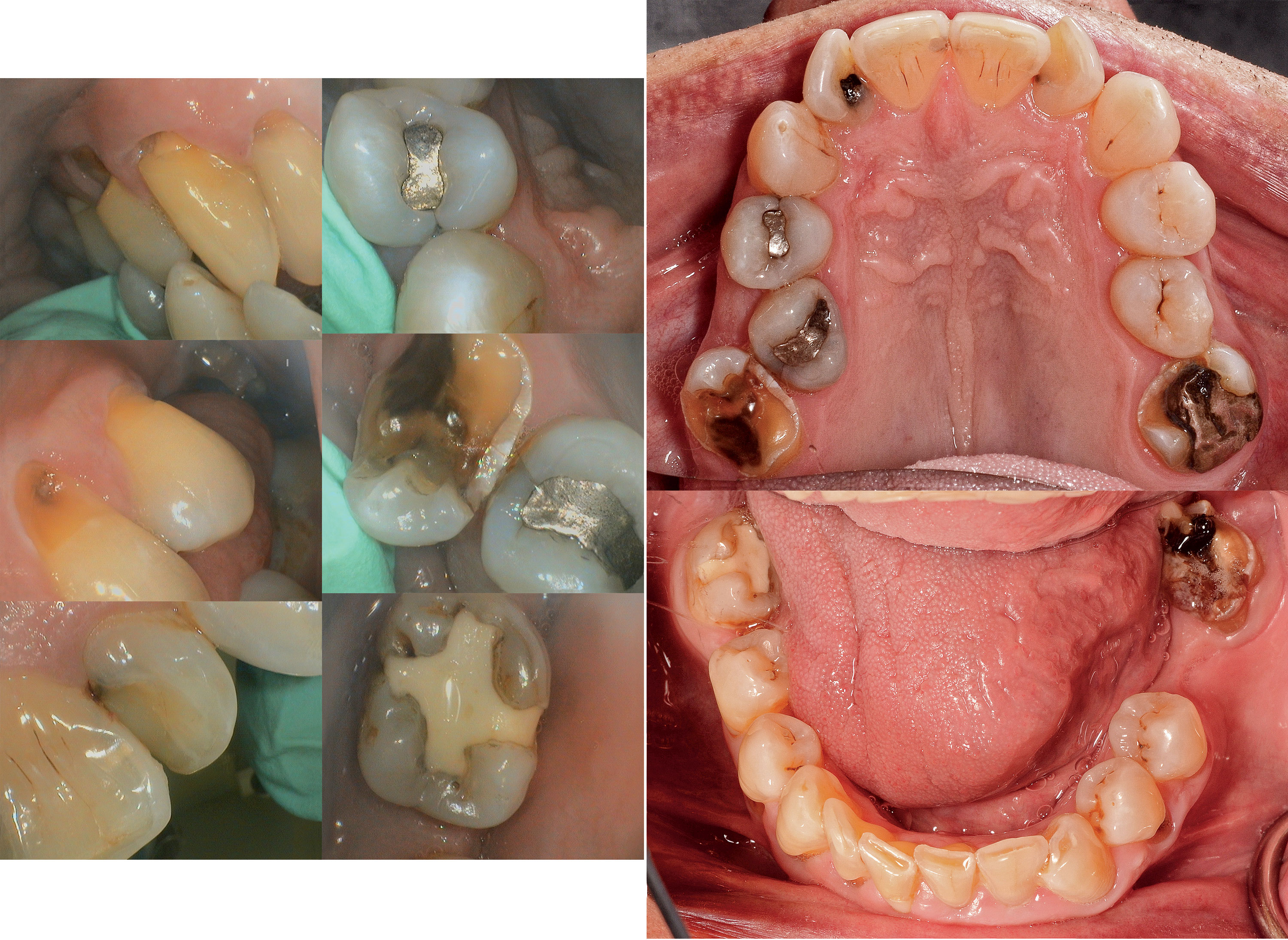

Images from an intraoral camera (left) versus images of the same patient using a DSLR camera (right).

Dr Sheridan’s interest in photography began long before his career in dentistry. When he was 12, he inherited the family’s Kodak Brownie camera after his father died. “There wasn’t much money for film,” he recalled, “but I practiced a lot and occasionally took photographs. I started my dental practice in 1971, and then I bought my first Nikon film camera and an 8 mm movie camera in the mid-1970s to record those magic moments of my kids growing up. I like instant gratification, so the delay between taking the photograph and receiving the finished prints or film a week or two later somewhat spoiled the photographic process for me. It was the excitement of digital photography and personal computers in the late 1990s that ticked all the boxes for me. I started to think that photography had a real place in dentistry as part of a digital suite of records.”

A self-taught photographer, Dr Sheridan’s crash course in photography came in 2005 when he decided to document the over 100 Art Deco radios he had been collecting as a personal hobby. Unable to find (or afford) a suitable professional photographer for the project, he decided to do the work himself and experimented with a barrage of technical photography equipment before settling on a simple and successful configuration: a camera, a bounce flash, and a tripod.

High-quality digital photographs can dramatically augment communication with patients regarding treatment concerns, especially in the posterior teeth.

“As I learned more about close-up photography,” Dr Sheridan said, “I realized that what I was doing in the surgery needed a complete update. At the time, most of the advice and teaching regarding clinical photography was based on outdated ideas from the film era and usually limited to anterior teeth. Our dental records are full of information, but there’s nothing that shows us exactly what we see in the mouth. I thought that clinical photography should add something significant to best practice in dentistry and also reflect reality. The images needed to be relevant and informational, of consistent high quality, and easily integrated into the workflow. I also felt that limiting clinical photography to the anterior teeth and cosmetic purposes was neglecting the bulk of everyday dentistry and taking the easy route. We are responsible for all of the oral tissues, both hard and soft, and even though photographing the posterior teeth is much harder, we need a system that allows us to comprehensively record the mouth as we see it.”

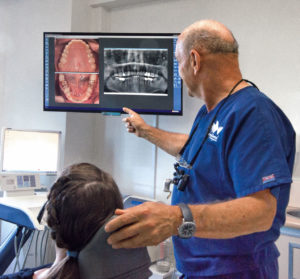

Dr Sheridan and members of his staff demonstrate how clinical photography involves collaboration between the photographer, an assistant, and the patient.

Dr Sheridan’s book, Clinical Photography in Dentistry: A New Perspective, outlines the system he has developed and is an accessible and comprehensive introduction to clinical photography for general dentists. The book covers the principles of clinical photography, recommended camera equipment and optimal settings, digital storage and management of the images, and standard views to be included in every patient’s record. The last chapter offers a structured approach to communicating with patients using the patient’s own clinical images, giving the dentist or hygienist an ethical and effective way to help patients make better decisions about their dental treatment. The book’s entry to the literature, which until now has lacked evidence of clinical photography’s value in general dentistry, is of significant importance.

Digital photographs can be integrated into the same software as digital radiographs so that they can be viewed side-by-side when assessing the case and educating the patient.

“Dentistry is a profession with a strong commitment to change being supported by evidence-based research,” Dr Sheridan said. “Unfortunately, there is little published literature about clinical photography in dentistry. Until now there has been nothing to prove to a naysayer that there is an academic and common-sense foundation for the routine use of clinical photography in dentistry. My textbook is the first to identify and show the range of uses for clinical photography. The idea of increased acceptance of treatment plans is not just an assumed consequence of using photographs. My book is an attempt to bring a measure of academic rigor to this field in order to substantiate clinical photography’s value as an integral part of our recording and communication tools.”

Dr Sheridan hopes that his book will reach a whole new audience of dentists, hygienists, academics, and students all around the world, giving them a complete and rational perspective on how clinical photography is part of best practice in dentistry and how it can become one of their most valuable and informative tools.

Peter Sheridan, AM, BDS, MDS, FICD, is a dentist in Sydney, Australia, and has been in private practice since 1971. He is a clinical lecturer in the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Sydney and presents courses, lectures, and master classes on clinical photography throughout Australia and New Zealand. His book, Dental Clinical Photography: A Guide to Standard Views (Bakelite, 2013) tailored the photographic protocol to general dentistry. He has a master’s degree in preventive dentistry and is a fellow of the International College of Dentists. Dr Sheridan is also an accredited professional photographer whose photographs and articles appear in specialist fine art journals, books, travel publications, museum catalogs, and print media. In addition, he is an internationally recognized historian, collector, and speaker on Art Deco design who has authored two photographic reference books on Art Deco radios, Radio Days: Australian Bakelite Radios (Bakelite, 2008) and Deco Radio: The Most Beautiful Radios Ever Made (Schiffer, 2014). In 2001 Dr Sheridan was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia by the Australian government for his international work in empowering people affected by multiple sclerosis.

Peter Sheridan, AM, BDS, MDS, FICD, is a dentist in Sydney, Australia, and has been in private practice since 1971. He is a clinical lecturer in the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Sydney and presents courses, lectures, and master classes on clinical photography throughout Australia and New Zealand. His book, Dental Clinical Photography: A Guide to Standard Views (Bakelite, 2013) tailored the photographic protocol to general dentistry. He has a master’s degree in preventive dentistry and is a fellow of the International College of Dentists. Dr Sheridan is also an accredited professional photographer whose photographs and articles appear in specialist fine art journals, books, travel publications, museum catalogs, and print media. In addition, he is an internationally recognized historian, collector, and speaker on Art Deco design who has authored two photographic reference books on Art Deco radios, Radio Days: Australian Bakelite Radios (Bakelite, 2008) and Deco Radio: The Most Beautiful Radios Ever Made (Schiffer, 2014). In 2001 Dr Sheridan was awarded the Member of the Order of Australia by the Australian government for his international work in empowering people affected by multiple sclerosis.

He welcomes questions and comments and is available to help dental professionals incorporate clinical photograph into their practices. peter@clinicalphotography.com